For the 6th step of the Wide Open Project, Léa moved to Africa, looking for positive ecosystems to meet the future challenges of the continent.

AN URBANISTIC

UNPRECEDENTED CHALLENGE

It must be said that the challenges are daunting: according to demographers, the African population will have doubled between 2010 and 2050 and the number of urban tripled. In only about thirty years, one in four humans will be African and the continent will house the 5 largest cities in the world, huge conurbations extending over several countries.

This phenomenon puts us in front of an unprecedented urbanistic challenge, the outcome of which could well seal our future for everyone. Africa can not be satisfied with a classical urbanism, too slow to absorb in such a short time such a human density, too static to create cities capable of transforming by a crescendo rhythm of our societies, and absurdly dependent on natural resources soon exhausted.

However, faced with this danger both ecological and migratory, the continent – whose pace of urbanization is currently the highest in the world (+ 3.4% per year on average according to ONU Habitat) – yet does not take the part of a green urbanism.

It is in this complex context that the Wide Open Project traveled to Togo, meeting the architect and anthropologist Sénamé Koffé Agbodjinou and the project “Hub City” that he created in 2012 with L’Africaine d’architecture. This project makes Lomé the laboratory city of a new model of participative urban planning, combining vernacular, urban acupuncture and hacker culture.

NO TO THE SMART CITY,

YES TO THE HUB CITY

When he mentions the concept of “smart city” or “intelligent city”, augmented by technologies, Sénamé Koffé Agbodjinou is not tongue-tied. He does not hesitate to talk about it as a concept to be overcome, an invention of IBM (and other major telecom groups) to sell their technologies everywhere, even if it means individualizing citizens and destroying nature.

However, everyone does not agree with him and the majority of African decision makers seek instead to build technological hubs modeled on western cities. They often go so far as to rival the height of their glass and reinforced concrete skyscrapers, hoping to attract investors and large multinational groups, like Lagos in Nigeria, now known as “the New York City of Africa”.

As an architect, Sénamé Koffé Agbodjinou is a defender of vernacular constructions. In other words, he advocates building according to the dynamics, the materials, the traditions, even with the complicity of the local populations, in complete contradiction with the internationalist system, which does not fit into any context.

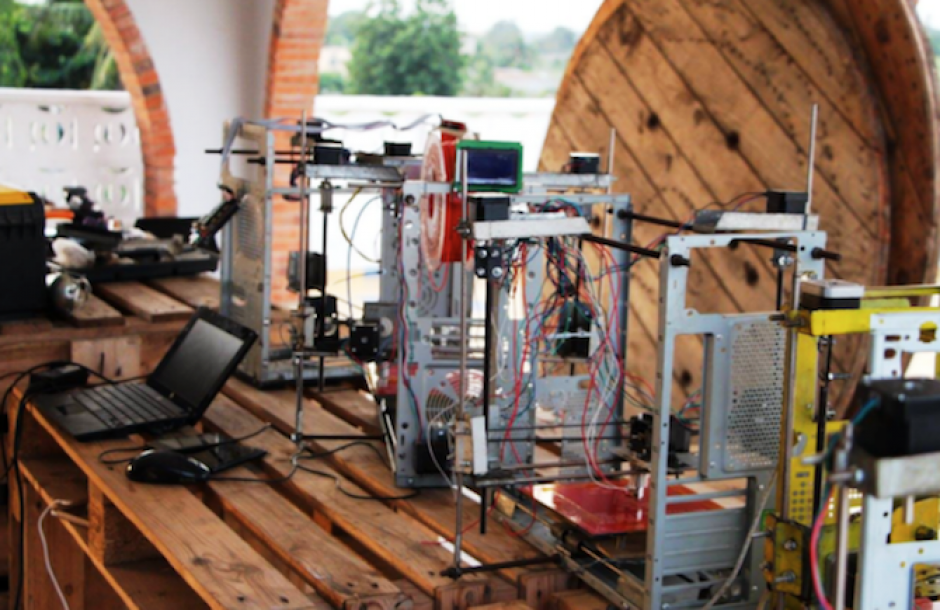

In 2011, while living in Europe, he discovered the first spaces FabLab and hacker culture. The click inside of him is strong: he sees there the potential to make the vernacular, not only on the scale of the building or the village, but that of the whole city.

He then decided to embark on a daring experiment: to make his hometown – Lomé – a full-size laboratory of a new approach to the city, a utopia he would call “hub city” and which would be vernacular in that everything the world would participate in building it, thanks to a network of technological third-places, rallying communities dedicated to the development of urban projects of proximity.

A MAILLAGE OF PLACES

FOR THE SMART CITIZEN

In 2012, Sénamé creates the first place of its urban program: the Woelab 0, still today the biggest tech-hub of the sub-region with its 600 m² of “technological democracy” aiming to make everyone face up to the digital revolution.

This space was thought by the anthropologist as a 2.0 version of the initiation pens. Community rituals rebuild the disappeared cohesion of the big cities. This FabLab has the unique characteristic of welcoming everyone, no matter how old or qualified: you can train there for free with new technologies and be accompanied on the creation of projects.

The young shoots that have become Smart Citizen together set up start-ups to solve local urban issues. Urbanattic is developing urban vegetable gardens, for example, while Scope is tackling the major problem of plastic waste. In the end, the urban factory is democratized: everyone can participate to build the reality of the neighborhood and more widely of Lomé.

In order to deconstruct the capitalist reflexes at the root and to anchor the collective and collaborative culture, the ownership of start-ups created in the Woelabs remains common to the entire community. The remuneration is established according to the level of personal investment on the project and any profit generated directly redistributed in the projects, thus avoiding any reflex of hoarding or accumulation, which individualizes every day more the urban Togolese.

By an approach called urban acupuncture, consisting as Senamé would say to “make small injections to specific places of the big sick body of the city,” the Hub City urban program consists of meshing the city of a number of Woelabs, which will each impact their local territory on a radius of about two kilometers.

Observe the city, identify reserves, unoccupied places with potential and create digital lungs. The principle is simple and replicates already: a second place, Woelab Prime, has already opened last year.

Eventually, a platform could strengthen this network on the city, by a system of points awarded according to his personal investment for the city, creating a new trading system in its own right, this time non-monetary. The potential is massive: if a hundred Woelabs gradually developed on the city, some 1000 start-ups would be created, all likely to multiply the GDP of Lomé. We are still far, but the impact is already there.

THE STRENGTH OF A UTOPIA

The Hub City experiment has not received any subsidies so far. However, six years after the creation of the first Woelab, utopia is still alive and its impact very tangible.

If the start-ups developed have positively changed their neighborhood, Woelab, among the very first FabLabs in the world, has also inspired the creation of much of the labs created in the region since. In fact, four young people in five in the Togolese tech scene have gone through the Woelab, which has become a real institution.

The next step for this visionary project is the creation of a third venue: this time a school for students at the end of design and architecture studies, to initiate a permanent construction site, linking theory and experimental practice.

While the number of architects registered in Africa is dramatically low, it is indeed urgent to train architects capable of thinking their cities differently and ready to accelerate this revolution of the urban factory.

This article is published in Hub Smart City